Stephen Sondheim: the man who transformed Musical Theatre

David Benedict

Friday, March 1, 2024

Sondheim biographer David Benedict reappraises his legacy through the lens of three pivotal works: Company, Sweeney Todd and Assassins

Poor Vincent Van Gogh. He died having sold precisely one painting during his lifetime. Mercifully, the only list of major 20th-century artists upon which the name Stephen Sondheim does not appear is ‘Unappreciated In His Lifetime’.

From the evening on 11 March 1973 when an all-star cast gathered to celebrate his already unique contribution to Musical Theatre in Sondheim: A Musical Tribute – a concert happily recorded and released – his position as an artist has been secure. As the years rolled along, it became increasingly clear that he wasn’t just an unusually highly skilled composer and lyricist, he was a dramatist. As much as contemporaries like Edward Albee or, a little later, August Wilson and David Mamet, he was one of America’s most singular and important theatrical voices. It’s just that his voice was also musical.

In the reactionary world of Broadway commercial theatre, Sondheim was a radical

That said, the breadth and depth of his talent was not immediately a talking point. Despite making his Broadway debut aged 27 with his first professionally produced show – a less-than-trifling matter by the name of West Side Story – his contribution to this milestone (deft, dynamic lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s knockout music) went unheralded. Indeed, it would be another 13 years before the Musical Theatre world sat up and noticed him.

The show that made that happen, Company, was groundbreaking in numerous ways. Musicals tend to deal in simple emotions but Company revealed Sondheim as the musical poet of expressive emotional complexity. His work brims with ambivalence and ambiguity. And what’s more, Company also began his unparalleled, uninterrupted run of six musicals over 11 years that changed the art form forever.

Maria Friedman's production of Merrily We Roll Along on Broadway (credit: Joan Marcus)

Maria Friedman's production of Merrily We Roll Along on Broadway (credit: Joan Marcus)

Of those headline-grabbing shows that followed it – Follies, A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd and Merrily We Roll Along – only the second was a financial hit, but what became ever clearer was that in the reactionary world of Broadway commercial theatre, Sondheim was a radical.

As a teenager, the budding artist had been mentored by his friend’s father, Oscar Hammerstein, who himself had changed Musical Theatre in 1943 when he and Richard Rodgers brought true characters and drama to so-called musical comedy when writing the first fully fledged musical play, Oklahoma! Hammerstein taught Sondheim the rules of the game and the apprentice then proceeded to not only find his own voice, but to make non-stop demands of both himself and his chosen art form, breaking the rules time and again in search of the new.

No two Sondheim shows are alike. The lavish Follies uses pastiches of songwriting in musicals to simultaneously celebrate and warn of the delights and deceits of nostalgia. Pacific Overtures, one of his least-known but most evocative shows, uses completely idiosyncratic orchestration to examine the opening up of Japan to American imperialism. Sweeney Todd is an alarmingly funny serial-killer thriller. The flawed Merrily We Roll Along, whose narrative runs backwards from cynicism to innocence, flopped badly, but its glowing score brims with heartbreak.

2023 production of Pacific Overtures at the Menier Chocolate Factory (credit: Manuel Harlan)

2023 production of Pacific Overtures at the Menier Chocolate Factory (credit: Manuel Harlan)

Although over his seven-decade career he made rare excursions into film and TV, Sondheim’s experimental spirit was singularly dedicated to the development of Musical Theatre. Unlike many artists who hit on a winning formula and then repeat it, to the advantage of both their reputation and their bank balance, Sondheim refused to stick with the tried and trusted.

His approach is summed up in the song he wrote for the 1976 Sherlock Holmes film The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. His deliciously arch number about a Madam recounting her bedroom exploits is entitled ‘I Never Do Anything Twice’ – and that’s the most succinct summation you’ll find of his ethos. Allergic to repeating himself, he forever believed in safety last.

Company (1970)

It’s hard to see now, but when it first appeared, Sondheim’s Company was revolutionary. Eight years earlier, in 1962, Helen Gurley Brown had surprised America with a non-fiction guide for young women seeking commitment-free independence. Within three weeks of publication, her Sex and the Single Girl had sold over two million copies. A paradigm shift, it began determining an entire generation’s views on marriage.

But if bookshops were happy selling something sociologically new and daring, life was very different on Broadway. In the traditionally family-friendly art form of musicals, sexual politics were abidingly conservative. The mindset finally began to crack in April 1968 with the counter-culture, let-it-all-hang-out hit Hair, but that was a maverick one-off. The real game-changer came exactly two years later with Company.

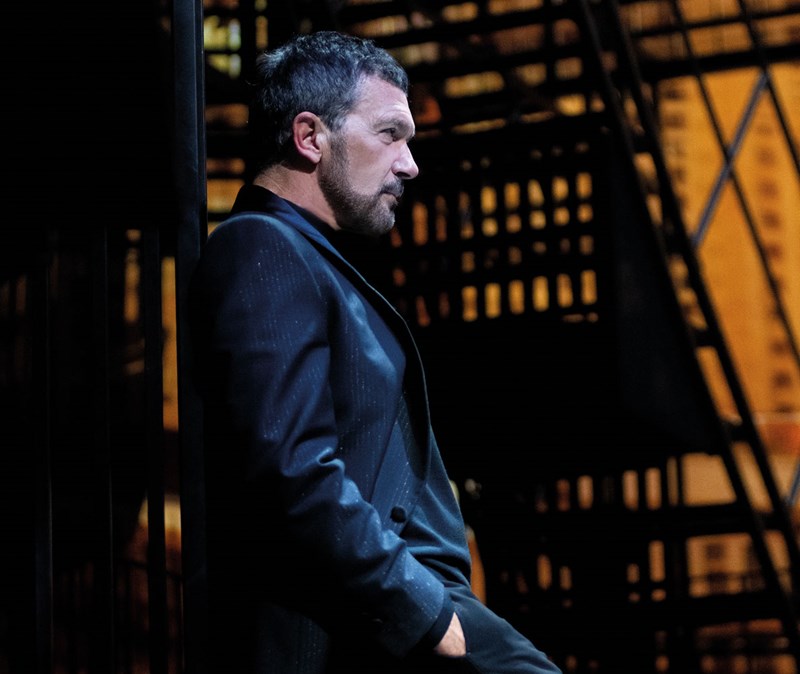

Antonio Banderas in a Spanish-language Company (2021) (photography: Photograph supplied initially by The Stephen Sondheim Society and taken by Javier Naval. The show ran at Teatro del Soho CaixaBank in Malaga; it was produced by Teatro del Soho CaixaBank and directed by Antonio Banderas / Matthew Murphy)

Antonio Banderas in a Spanish-language Company (2021) (photography: Photograph supplied initially by The Stephen Sondheim Society and taken by Javier Naval. The show ran at Teatro del Soho CaixaBank in Malaga; it was produced by Teatro del Soho CaixaBank and directed by Antonio Banderas / Matthew Murphy)

It didn’t just abandon the Broadway standard ‘boy gets girl’ content, it pivoted around a boy who isn’t even looking for a girl. Putting the ‘man’ into Manhattan, Bobby, the central character, is casually seeing not one but three women. But on the occasion of his 35th birthday, and facing down a slew of well-intentioned birthday messages and a threatened surprise party from ‘These good and crazy people, my married friends’, he finds himself taking stock. Sondheim, bookwriter George Furth and director Hal Prince fashioned a musical in which Bobby asks himself: Where am I? Where might I be heading? Is commitment a dirty word? Should I be thinking about…marriage?

Yet more remarkably, the creators found a completely new way of telling the story – by abandoning the very notion of story. Company doesn’t have a traditional plot, it has a conceit: the entire show takes place in a single moment in Bobby’s head as he looks at the lives and loves of his friends – who, in turn, are all asking why this eligible guy is still single. Like a diamond cut at multiple angles, Company looks at commitment from a host of perspectives.

It was 1970 and they were writing a show about ‘now’. It felt cool and, remarkably, it still does

The show's witty, bracingly unsentimental and sophisticated approach marked it out as something new: Musical Theatre for adults. And all of that is brought to musical life by Sondheim’s forward-looking score. From its opening bars, he and orchestrator Jonathan Tunick created a contemporary, upfront, urban sound with an orchestration featuring everything from bright brass to lots of percussion – glockenspiel to drum kit – and, crucially, electric guitar. It was 1970 and they were writing a show about ‘now’. It felt cool and, remarkably, it still does.

The show is, unassailably, Sondheim’s first mature score. Rather than advancing the (non-existent) plot, the songs exist as mostly wry comment, snappily and memorably skewering marital mores. And almost all of them, not least the drily sarcastic ‘The Little Things You Do Together’ – a kind of Women and Men Behaving Badly – and the men’s exquisitely rueful ballad about marriage (‘Sorry-Grateful’), promptly wrote themselves into Musical Theatre history.

Marianne Elliot's revolutionary gender swapped 2018 production at the Gielgud Theatre

Marianne Elliot's revolutionary gender swapped 2018 production at the Gielgud Theatre

Sondheim created the all-knowing, much-married character of Joanne for Elaine Stritch, the high priestess of droll, and gave her the sockeroo 11 o’clock number: ‘The Ladies Who Lunch’, a phrase that went straight into the lexicon. Its deliciously vicious bitterness and building drama make it one of his most enduring songs. If that weren’t enough, it’s promptly followed by the climax, ‘Being Alive.’ Bobby finally relaxes his defences and, in the course of the song, has a revelation that he is ready for commitment.

To the delight of the initially mildly sceptical Sondheim, Marianne Elliott’s recent gender-switched rethink of the show – in which, with only the tiniest of script tweaks, male Bobby became female Bobbie (Rosalie Craig in London, Katrina Lenk on Broadway) – made complete, multi-award-winning sense. In 2022, as if in tune with Sex and the Single Girl, while almost no single man has a clutch of friends persistently worrying about why he isn’t in a long-term relationship, almost every single woman does. It proved, half a century on, how astonishingly immediate the show remains.

Company Original Broadway Cast Recording (1970)

Dean Jones only played Bobby for a couple of months before exiting the show, but he had time to record this zinger of a cast album. His aching performance is supported by a matchless company – including Elaine Stritch and her landmark reading of ‘The Ladies Who Lunch’. The most recent re-release has the considerable bonus of Jones’s replacement Larry Kert in a wonderfully easeful ‘Being Alive’.

Sweeney Todd (1979)

Film director Wes Craven hit box-office dynamite inventing comic slasher-movies in 1996 with Scream and its sequels. But Sondheim similarly blended humour and extreme violence to create an audacious masterpiece almost two decades earlier.

Whichever way you slice it, Sweeney Todd is a gory glory and was the single biggest gamble of Sondheim’s career

Michael Ball as the blood-thirsty barber in the Chichester Festival Theatre's 2011 production (credit: Catherine Ashmore)

‘Well, yes, of course we could do that. I don’t suppose he’s got any relatives gonna come poking round looking for him…’ And as a high, plucked chord in the orchestra rings out, she stops to wait for him to catch her drift. As Sondheim recalled, ‘Fifteen hundred people gasped. I clapped Hugh on the knee and said, “We did it!” It proved they were in on the story. If you asked me to pick the most satisfying moment at any of my shows, the exhilaration of that moment would be one.’

That thrilling tension derives from Sondheim’s extraordinarily dynamic musical storytelling, beginning with the chorus whose driving, threatening ‘The Ballad of Sweeney Todd’ – a reworking of the traditional Dies Irae (day of wrath) plainchant – opens the show and is then threaded throughout. This helps narrate the tale of the brutal barber. Fifteen years earlier, he was transported to Australia by a judge who, lusting after Sweeney’s wife, sent him away for a crime he didn’t commit. As the show begins, Sweeney returns to Fleet Street with a new name and a mind bent on revenge. And he and Mrs Lovett hatch a plan which comes within a whisker of success…

Surprising, exhilarating moments are two a penny in this huge and hugely venerated musical. Whichever way you slice it – and there’s a whole lot of slicing – Sweeney Todd is a gory glory and yet was the single biggest gamble of Sondheim’s career. He took the darkest, most dangerous material ever handled in a Broadway musical (drawn from a play with songs by Christopher Bond that he’d seen at London’s Theatre Royal Stratford East) and rewrote it into nothing short of Cannibalism – the Musical. He made it not just palatable but a giddy pleasure by raising laughter amid the slaughter.

Singing usually slows everything down, but despite 80 per cent of the show being sung, Sondheim pulled off the considerable trick of keeping everything tense. Most musicals are low on engaging plot but Sweeney Todd is wonderfully taut with huge, unexpected plot reveals. It more than lives up to its subtitle ‘A Musical Thriller.’

Musically, Sondheim blends all manner of elements. He was intent upon creating the stage equivalent of a horror movie, its mood stemming from Bernard Herrmann’s score for the 1945 chiller Hangover Square – which 15-year-old Sondheim experienced twice in one day, rushed home and then played on the piano. His writing for Mrs Lovett (created by Angela Lansbury) derives from musical comedy; the music for Sweeney himself is more operatic. He binds all these highly coloured, atmospheric elements together into what is arguably his masterpiece, its cumulative power made plain by the dazzling second half of Act One.

The judge’s guilt-and-lust-filled solo ‘Johanna’ slides into the young lovers’ escape duet, ‘Kiss Me’. That’s immediately followed by a duet for the beadle walking the judge to Sweeney’s shop in ‘Ladies in Their Sensitivities’. Those duets are then combined into a thrilling quartet – described by the late opera critic Rodney Milnes as the finest since Rigoletto – before ‘Pretty Women’, the serene but danger-filled duet between the judge in the barber’s chair and Sweeney wielding his razor. At the last second, the judge escapes and Sweeney explodes with rage in his fiercely soul- baring ‘Epiphany’, before Mrs Lovett lassoes him into her dastardly plan in the rhyme-fest first-act finale. That unstoppable succession of numbers alone would secure Sondheim’s status as the master.

Sweeney Todd Original Broadway Cast Recording

There are few recordings of Sweeney Todd because the staggeringly atmospheric two-CD original cast recording is unsurpassable. Paul Gemignani conducts Len Cariou, Angela Lansbury and the company in a thrillingly immediate performance.

Assassins (1990)

There’s highly conscious irony at play, but the single most thrilling moment in Assassins is a tiny, scarily charged-up moment of silence. In ‘The Gun Song’, Charles Guiteau, the deluded man who shot James Garfield, the 20th President of the United States, brandishes a gun and sings, to a surprisingly jaunty waltz melody: ‘What a wonder is a gun! / What a versatile invention! / First of all, when you’ve a gun …’ At which point shocked silence grips the theatre as he aims the gun directly at terrified audience members, before triumphantly singing: ‘Everybody pays attention.’

Henry Goodman and Anthony Barclay in Sam Mendes’s Assassins at the Donmar Warehouse, 1992, and the production poster (credit: Catherine Ashmore)

Henry Goodman and Anthony Barclay in Sam Mendes’s Assassins at the Donmar Warehouse, 1992, and the production poster (credit: Catherine Ashmore)

In a country (now even more than when the show opened) tearing itself apart over gun culture, that moment and its release of relieved laughter afterwards, perfectly conceived and crafted by Sondheim, illustrates his musical command of drama – and Assassins has plenty of that. Like Company, it’s plotless, but where the earlier show was a scintillating study of fear of matrimony, Sondheim and his bookwriter John Weidman up the stakes considerably in their small but mighty study of malice aforethought. Their unlikely-sounding musical is a cross between a rogues gallery and a shooting gallery, portraying the terrifying, logical conclusion of American individualism. Or, as the opening song puts it, ‘If you keep your goal in sight / You can climb to any height / Everybody’s got the right / To their dreams.’

Assassins asks us not to sympathise with its gun-toting outcasts but to consider why they did what they did

A wonderfully compact, increasingly vivid, one-act theatrical song cycle of illusions and delusions, Assassins has an unusually mordant tone which is scarcely surprising since the principal cast comprises nine disparate people who have assassinated (or attempted to assassinate) American presidents. But far from excusing their heinous behaviour, the piece holds their motives and behaviour up to beady-eyed scrutiny, seeking to explain what spurred them and what in American culture made it possible.

Its 100 years of history are reflected by an equivalent panorama of period styles of American music. There are folk songs from the Southern hills and snatches of John Philip Sousa marches, especially ‘Hail to the Chief’. The latter, the official Presidential Anthem of the United States, operates as a theme throughout and opens the show as a seductive waltz, played on a calliope to set up the carnival atmosphere. There are conscious echoes of Stephen Foster’s songwriting; Aaron Copland-style fourth and fifth intervals are put to dramatic use in bold accompaniments; ‘The Gun Song’ even uses the ultra-American form of the barbershop quartet to deliciously ironic effect.

Misguided though its characters were – and Assassins is definitely character-based – most of them did what they did out of some form of love, albeit hideously warped. As a result, the score is unafraid to wear its heart on its sleeve, though in seemingly unlikely ways. Sondheim supplies a beguiling, deliberately corny duet, ‘Unworthy Of Your Love’, for the two youngest characters that might have been recorded and sung by The Carpenters, had the sentiments not been those of John Hinckley Jr, whose maniacal obsession with Jodie Foster led him to attempt to kill Reagan, and Squeaky Fromme, an acolyte of mass murderer Charles Manson, who took a shot at Gerald Ford.

All of that is bookended with upbeat traditional musical comedy, the light, sweet strut of the opening number, ‘Everybody’s Got The Right’. Sondheim describes it as a ‘prototypical, optimistic American musical number, albeit with a double edge’. That serves as a route into the show as a whole. Assassins asks audiences not to sympathise with its cast of gun-toting outcasts, but to think twice about exactly why they did what they did.

That he and Weidman make their argument so startlingly entertaining is one of multiple reasons why this musical is so high on Sondheim’s list of achievements. He held the piece unusually dear, rightly believing it to be one of his finest.

Assassins Original Broadway Cast Recording

Joe Mantello’s chilling Broadway production, conducted by the original musical director Paul Gemignani, boasts zinging, ideally characterised performances in a more complete version of this knockout show.

Late Sondheim

The latter half of Sondheim’s career, characterised by pioneering musicals like Assassins, stands as a rebuke to F Scott Fitzgerald’s maxim ‘There are no second acts in American lives’. As he grew older, far from retreating, Sondheim became more, not less, experimental. Moving away from the constraints of commercial theatre, he began working Off Broadway and found new ways to use music and lyrics to explore ideas theatrically.

Sunday in the Park With George, the first of Sondheim’s several collaborations with writer/director James Lapine, is a musically pointillist depiction of the creation of a Seurat painting and a fascinating portrait of the art of making art. Into the Woods wove a host of fairy tales together to illuminate self-fulfilment versus selflessness. Assassins, as we’ve seen, is a dark-hearted vaudeville looking at the American cult of individuality.

Sondheim at the Royal Opera House Sweeney Todd dress rehearsal in 2003 (credit: Catherine Ashmore)

Until Sondheim came along, no one made musicals out of subjects like these. And while the best writers have no wish to sound like him – a true artist develops their own voice – his lifelong delight in expanding the art of the possible has influenced every writer interested in fresh ideas who has followed him.

Throughout his career, Sondheim was insistent that his shows were anything but autobiographical. He was not, he argued, in the business of exposing himself: he was writing characters in specific dramatic situations. But, as with most artist’s statements, one should trust the work not the artist. He conceded that the closest he got to autobiography was his song about the precision and exhilaration of artistic creation, ‘Finishing the Hat’, from his 1984, Pulitzer Prize-winning Sunday in the Park With George. The show’s final line is a diary entry about the title character. But it’s hard not to hear Sondheim’s own voice in there too: ‘White: a blank page or canvas. His favourite – so many possibilities.’

Never miss an issue of Musicals magazine – subscribe today

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN ISSUE 1 OF MUSICALS (OCTOBER 2022)